In collaboration with Jambu Palaniappan, who led international expansion for Uber and eventually ran UberEats for EMEA. Jambu is currently the Managing Partner at Omers Ventures investing in early stage ventures in Europe.

Thanks to Joylita Saldhana for helping us structure and edit this post.

—

2020s: Virtual brands are going to go vertical.

You’ve read that physical restaurants are over. And they may be. But virtual restaurants are about to go vertical. In the coming years, we will see wide-ranging restaurant concepts (often delivery-only) scale their concepts to many cities, and even countries with great ease.

We will outline general principles & tactics you can use as you think through expansion.

Why now?

Typically, it has been difficult for successful restaurants to expand outside their home cities since they’d have to invest in real estate, hire staff, manage operational complexity of a new market etc.

Fast food chains were the exception. They achieved the level of operational sophistication and standardisation necessary to expand to other cities. This gave us pizzas and hamburgers, but more diverse cuisines or experimental menus were hard to scale beyond the iconic single restaurant.

With virtual kitchens and food delivery apps -- it is possible to quickly launch new locations. You can quickly kickstart operations out of a virtual kitchen and get widespread distribution with consumers by partnering with a delivery app.

The next McDonald’s could be a healthy salad brand. Brands like Grain (Singapore) Sweetgreen (USA) are already leading the way.

Source: Techcrunch

Let’s start with a backstory from Jambu about launch.

It's Christmas day 2013.

Back in the day, a job listing or a social media post by an employee of a ridesharing company was a strong tell for where they were going to launch next.

In one such post, a competitor’s employee posted something from Ireland. We figured this could only mean that that they were to launch in Ireland next.

Going first to market was a competitive advantage. So the launch team went into overdrive. Anthony El-Khoury parachuted into the city the next day and had Uber up and running in the city on January 10, 2014 — 14 days later.

It was only much later that we learnt that the competitor had no plans of launching there and the post by their employee was made while they were on vacation.

The story is funny and can easily be dismissed as a silly decision. But it is what allowed Uber to expand to hundreds of cities and become a global company while competitors remained regional.

It demonstrates the speed with which teams can execute expansion once the expansion playbook is written. Fortunately for Uber, the product worked everywhere so no city was a mistake.

We had a small celebratory dinner and got back to work.

(In my defence, I did try to get better pictures. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯)

On the Importance of Product-Market Fit

When you see startups like Uber and AirBnB expanding with ease, it’s easy to miss the main driver of such growth: product-market fit.

Uber enjoyed incredible product-market fit. People loved the convenience of booking a ride on an app as opposed to waving down a taxi or haggling with a tuk-tuk driver.

Given how superior it was to the alternative, customers were very ‘sticky’. In the context of virtual restaurants, getting your product (food, menu, brand) right and consumers hooked is a prerequisite to expansion.

In tech speak, this was called negative churn. Negative churn is “when current customers are spending so much additional money on your services that your churn is offset by it.”

Rule 1: Don’t Do It Till The Home Market Works

At least, don’t do it for the wrong reasons. Some people travel to run away from their problems. Some startups do the same thing. And that’s a bad motivation for expansion.

It may seem like a good idea to try your business model out in a different country; one that may seem more attractive for whatever reason (eg., consumers are more “sophisticated” in insert_city).

It’s very rare for an operation that’s failing in its home country to do a volte-face in an international location.

Conversely, home market success doesn’t guarantee expansion success either. In the early 2000s, Carrefour - a successful French retailer launched in Japan with 8 stores after extensive due diligence but failed to take off.

Localisation is a key dial

Localising your product (menus, food, ingredients) will be a key variable to your success. In Uber’s case, accepting payments by partnering with local solutions around the world was key to successful expansion.

Overlocalization.

Upon entry to the market, consumers anticipated Carrefour would represent luxury French products for which there was a demand. Instead, Carrefour followed their internationally successful strategy of working with local suppliers for goods common to the local market. Unfortunately, the market for local products was saturated thus Carrefour held no advantage over established retailers.

Underlocalization.

Carrefour also miscalculated the desire for service and appearance to the Japanese consumer. Carrefour sacrificed store appearance for shelved product maximization. Japanese consumers associate low-price with cheap-quality and prefer instead retailers who provide entertaining shopping experiences and products which enrich their lives.

Rule 2: Don’t rush it till it’s repeatable.

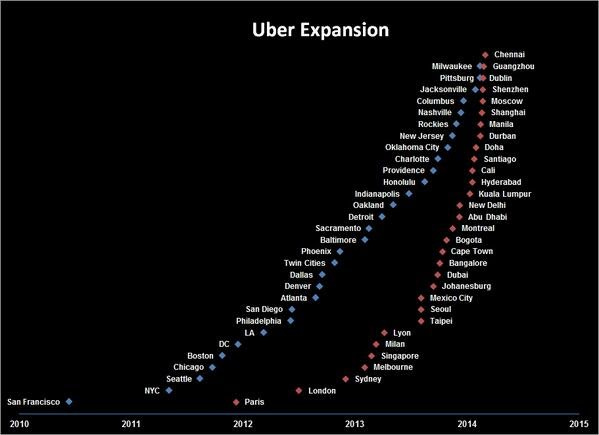

Image source: Business of Apps.

If you must do it, don’t rush it. As you can see, San Francisco is where it all began in 2010.

Uber’s second city, New York, shows up only a whole year later. There on in, the company saw near-hockey stick growth through cities in America.

The first foreign city, Paris, came along about a year and a half into the company’s existence.

Once we had it right, we could move really fast — as you can see — locations as diverse as Manila, Dublin, Shenzhen, Chennai, and Moscow were all added to the list almost concurrently.

At peak capacity, Uber’s launch team was lighting up one city per week.

Questions to Ask Before Expansion

If you are convinced that expansion is both inevitable and desirable, here’s a few questions to ask yourself before proceeding.

Have we got our product right?

Have we got the launch process repeatable?

Do we understand what is different about the new market?

Do we have the team?

Is it worth it?

Already feeling successful in your first location is a sign that you’re ready for expansion. We suggest looking up the below metrics — we’re skipping the explanations since they are a google search away.

Uber’s Greenlight Document and Process.

The Launcher. Uber had a special role called a launcher. They’re highly tactical generalists tasked with getting the business up and running in a short period. The launcher “has the responsibility of creating something where previously there was nothing, and sometimes in as little as four days”.

Launchers drop in, get a grasp of the transportation ecosystem, any relevant regulation and then they’ll do everything from building a pricing structure for that city to negotiating office rental and find our initial supply of drivers for the platform. The launcher typically spends eight weeks in a city, sometimes shorter, we’ve done a couple of cities in just four or five days.

This low overhead model allowed Uber to scale to multiple cities quickly and cheaply. The non-obvious point here is that you don’t need more than one person to run a launch if you have your product, process & partners in order.

Greenlight. Greenlight was a process by which we evaluated new markets and launched them. The purpose of the green light process was to identify “deal breakers” — reasons to enter or not enter a particular city. Remember everything at the early days of Uber was at the city level.

It is a run down version of all the data we can collect on a market top-down (available from research) and bottoms-up (collected from the city via in person conversations) rolled into a short slide deck.

Top-down Non-Negotiable Conditions. We started by asking ourselves in cities that are successful Uber cities, what do we have that makes our product successful? Ultimately, it came down to 3 non-negotiable conditions.

Ability to grow supply: can we scale the number of cars on the road? Are there enough eligible cars in the first place?

Ability to control price: can we ensure we have flexible pricing, and are not limited by pricing restrictions? Dynamic pricing allowed us to bring more supply onto the roads during periods of high demand.

Infrastructure: regulatory and payments infrastructure due diligence.

Ask yourself: what are the non-negotiable conditions you need to enter a new market? A real estate partner? virtual kitchen infrastructure? low-cost delivery networks? A local team?

Bottom-up Meetings. This often involved meeting with many transportation companies (to understand if we’ll meet political opposition), local regulators (to understand nuances we cannot gather from reading the law), tech companies (to understand the culture of the city) and potential candidates (to evaluate what sort of people we should hire).

Build a spreadsheet of individuals and companies from various categories that are relevant to your business and meet them. In these meetings, you’ll always learn more than you knew. The post-pandemic version may unfortunately mean more Zoom calls.

Get to Go or No Go. Ultimately the output of those early trips was a really tight green light document (a slide deck), that led to a “go or no go” decision.

Block a “Greenlight meeting” (at Uber they could often go on for 90 minutes) where the launcher pitches the launch of the city to a small leadership team. Use the meeting as a forcing function to make a decision. Ensure you have the smallest group of people on the call necessary to make a decision.

In our next edition, we will cover Shivam’s questions in more detail and the actual expansion process under the questions outlined earlier.

Subscribe for timely delivery!

—